Precedent Ready Go

Or President Rhettie, Go!

This is a little complicated maybe, and I’m unsupervised, which means it might be merely indulgent. I do worry that I’m too indulgent sometimes, at least in these last several years. I have been called a savor-er, after all, and that’s probably an indicator. And too candid sometimes, something I’m feeling bad about today actually. If you’re looking for something cuter and less, what…lofty (?), Jeanne really liked the last post and poem, Meant to Be—From a Christmas Tree. (I decided it should have read —From a Christmas Tree rather than —In a Christmas Tree.)

Just before the dawn of this phase of This Project, I indulged in a conversation about personal significance vs. the more beneficial positive precedent, in terms of value to society. As I recall, beer was in our veins by then, and the standard was set somewhat low for Relevance to This Project. Also the vagueness or overlap of those two concepts wasn’t an obstacle, just like it won’t be here, if you’ll allow it. Later I decided the discussion was really very relevant to This Project.

Actually, I’m not sure the personal significance ethic is primarily concerned about value to society, other than what would be maybe implied by the fact that significance is awarded by society. Positive Precedent vs. Personal Significance. Hmm. Okay, maybe the two terms are too appley-orangey. But they are not to Bug Stu, it just takes some imaginative charity and explanation.

7th Pie Theory has always been about precedent, just like a Bright Spot is about precedent—know what I mean? (A Bright Spot is not some made-up Stuism, as this link explains.) A Bright Spot is an example of positive deviance, the geeks call it, and not too rigidly defined nor too delineated, just something which demonstrates that something effective can be done regardless of perennial apparent insurmountables. It’s imperfect, but it still has its appeal and maybe even a magnetism besides the brightness, like brightness that flying insects are said to like.

The attribution to mere liking turned out to be a totally mistaken idea about insects, as long-time readers here might remember (nice nerdy video at that link—short). It was about an orientation mechanism for responding to the lighter sky and darker earth. That’s big, and it’s even bigger as a useful metaphor for us humies, Stu would say.

Related I swear, in the world of markets and marketing, there are active severed Invisible Hands* of Adam Smith like I mentioned around Halloween in The Could Life issue (in the third paragraph below the first picture and later, just before “How Santa Clause Got Saved In The Nightmare”—which is about the importance, the truth, of daring to be there for when opportunities arise).

The invisible hand is a metaphor inspired by the Scottish economist and moral philosopher Adam Smith that describes the incentives which free markets sometimes create for self-interested people to accidentally act in the public interest, even when this is not something they intended. Smith originally mentioned the term in two specific, but different, economic examples. It is used once in his Theory of Moral Sentiments when discussing a hypothetical example of wealth being concentrated in the hands of one person, who wastes his wealth, but thereby employs others. More famously, it is also used once in his Wealth of Nations, when arguing that governments do not normally need to force international traders to invest in their own home country. In both cases, Adam Smith speaks of an invisible hand, never of the invisible hand.

Going far beyond the original intent of Smith’s metaphor, twentieth-century economists [emphasis mine], especially Paul Samuelson, popularized the use of the term to refer to a more general and abstract conclusion that truly free markets are self-regulating systems that always tend to create economically optimal outcomes, which in turn cannot be improved upon by government intervention. The idea of trade and market exchange perfectly channeling self-interest toward socially desirable ends is a central justification for newer versions of the laissez-faire economic philosophy which lie behind neoclassical economics.[1]

The Distortions Came Quickly

You could say the liking, which is what markets depend on now, not to say prey on, always, is a mere element of, or an epi-phenomenon of, the more comprehensive wiring to flourish—both as an individual and with others and even future generations, at least the kids and grandkids.

Our liking isn’t really a choice, at least it doesn’t feel like it to me. The choice comes in the decision of what to do with that liking. We have to keep in mind that the market makes up the culture more and more these days, so that like-focused emanation “from above”, the culture making market, is more powerful, especially now that it’s entered the love-making, friend-making, influence-making realm. More and more artificial lights, you could say, designed to misuse a complex network of impulses towards something higher, more integrative.

Bug Stu refers to this as part of the Paradox of Ontological Disassemblies, that phenomenon in which elements of life that are part of an integrated whole are disassembled for the sake of understanding, ideally, or for the sake of exploitation, often by parasites, he says with a wry beetle grin. Whether those elements get swelled up or belittled by over-consumption, they do not go back into the integrated whole very well, and the whole is distorted by the…distortions. Dis-ease ensues, per Stu’s…understanding of our underbelly(ies).

The severed hands of the market help with the problematic separation of well-integrated function and liking, I mean. Liking is, like, vulnerable…to cancer, artificially induced and metastasized.

Believe it or not, all that was a way to explain, or at least explore, the difference between our attraction to pleasure or amusement (parts of an integrated whole) vs. our truer and wholistic “attraction” (really for orientation and information gathering) to Bright Spots. The terms can get confusing, like with everything. Sometimes it’s the terms that do the confusing, and not by accident. Here, if it is confusing, at least it’s accidental.

PRESIDENT RHETTIE GO!

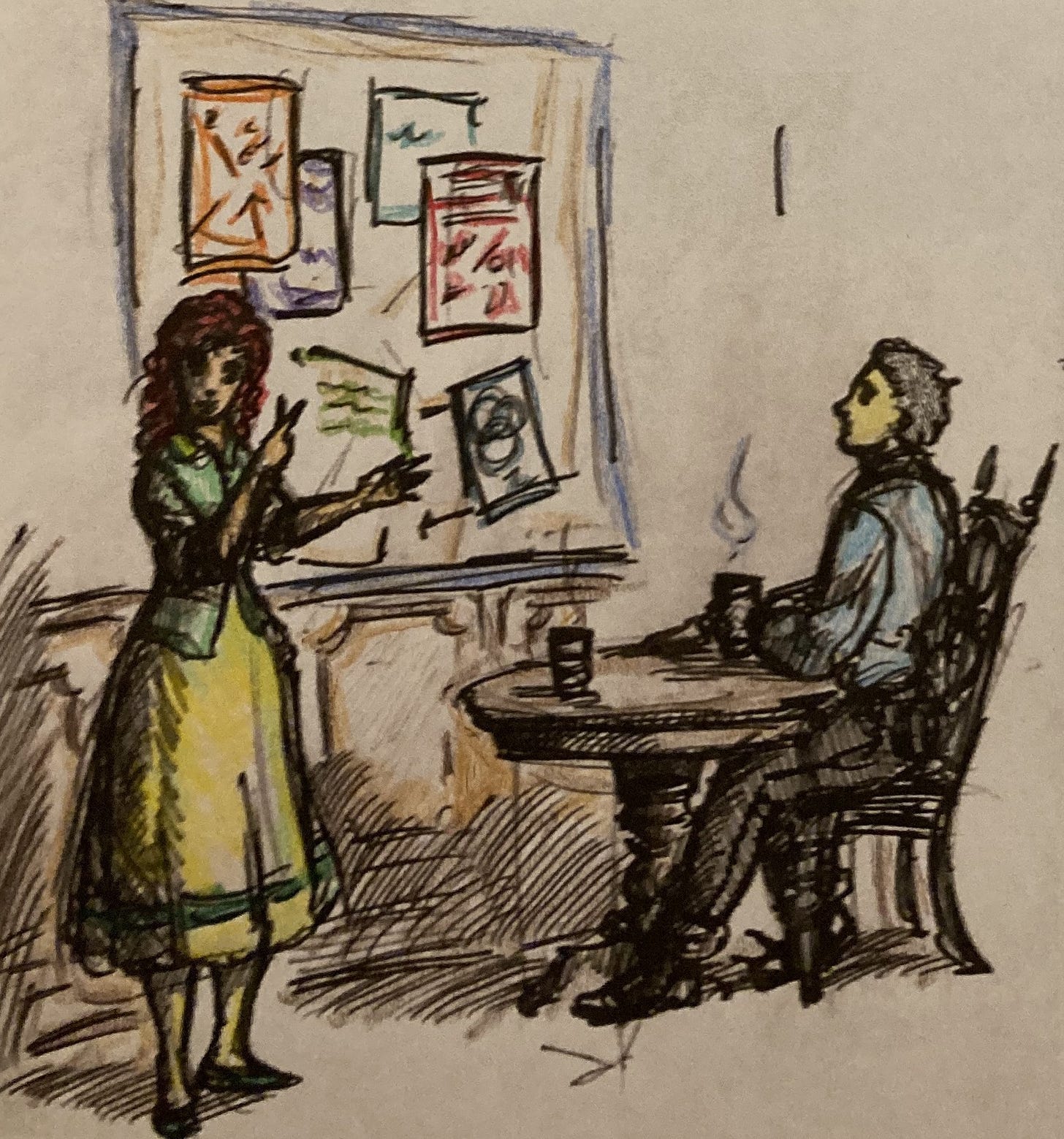

Okay, maybe it’s not the best time to talk about strategies and powers of presidents. Or maybe I could have just not brought that up and this would have been fine. But see, Wally has talked before about Rhettie’s Army. He even designed an emblem with a star in a circle, like our WWII emblems, back when we knew who and what and why and where the Enemy was.

“What we need are Bright Spots,” she had said to him. Thus, the star was born. And there are lots of ways stars have been used in this story. There’s the Star Eyes, the star on a Christmas tree, the stars you can see in the countryside but not in the city, the five-pointed Bright Spot rural development model, even “Champagne Supernova” from Oasis. all mentioned in the last few months here. I could go on.

But yes, Rhettie is about setting a precedent, in the way of a Bright Spot. Not personally, but on Earth in the Middle of Nowhere and in the galaxy (of thought, of possibilities, as a vine).

Rhettie was named after Margaret Fuller, the famous Transcendentalist, but her Grandma Dorie never liked that. She once quipped to a friend, “They might as well have named her after Ayn Rand” (not knowing that was her parents’ first thought until they realized the confusion that would come with the name Ayn).

Dorie is the one who created the nickname Rhettie from Margaret—not the most intuitive connection, which was her intent. Dorie was no fan of the Transcendentalists, much like the more surprisingly skeptical Louisa May Alcott, daughter of co-founder-ish Amos Bronson Alcott, and the author of Little Women.

In short, skipping a few unwritten chapters here, Rhettie realized that “What has made Is be,” Bug Stu’s obsession, along with “Qualifying the Quotidian,” can be traced back to a mere liking of the Transcendentalists, like insects circling a light, or ten, but never understanding why, and proceeding anyway.

That’s fine for a while. Then we’ll realize we’ll need to understand Bright Spots better, according to Stu, according to Rhettie.

Rhettie for President, according to Wally.

Thanks for reading : ).

Tim